Lower Back Pain and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

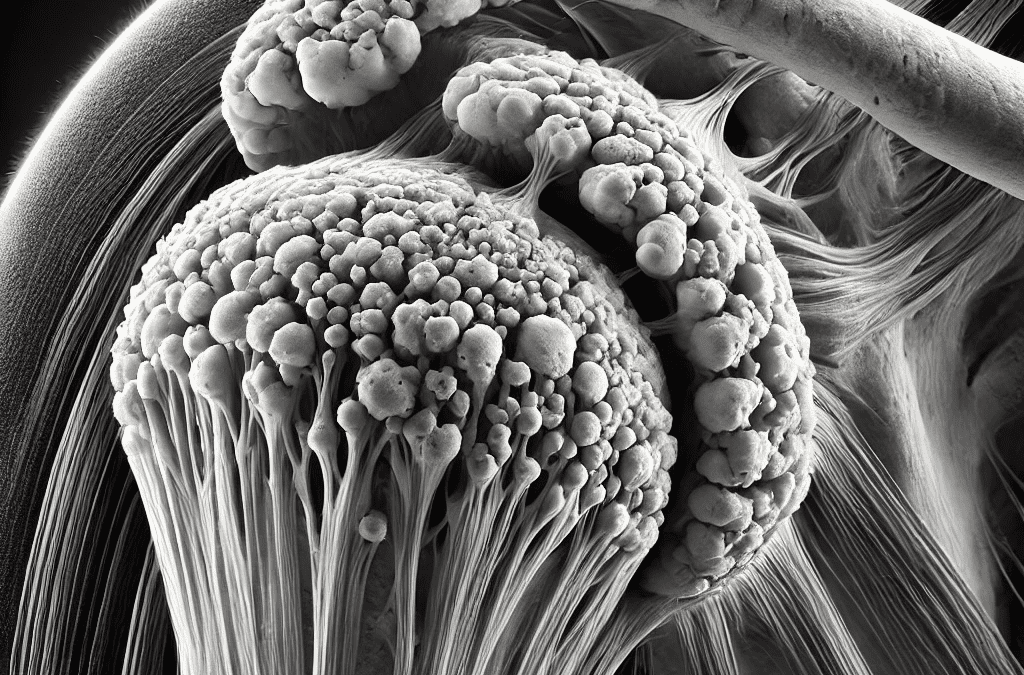

Lower back pain (LBP) is the most prevalent musculoskeletal injury, as approximately 80% of the population will experience LBP in their lifetime (Arab et. al 2010). Transverse abdominus activation is often prescribed for LBP however pelvic floor muscle (PFM) is not always incorporated into treatment. PFM aids in supporting the abdominopelvic organs and there is an abundance of research on the role of the PFM in urinary and fecal incontinence. Nevertheless, it is important to remember the PFM role in lumbar and pelvic stability and intra-abdominal pressure (Mohseni-Bandepi et. al 2011). Research illustrates that the combination of pelvic floor exercise alongside routine treatment can provide significant pain relief in LBP compared to routine treatment alone (Bi et. al, 2013), demonstrating the importance of PFM exercises.

The link between LBP and PFM helps to provide insight into the correlation between LBP and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). PFD is an umbrella term to describe weakness, poor endurance and hypertonicity of the PFM which can impact incontinence, prolapses and pelvic pain. Dufour et al. found that 95% of women with LBP had PFD, ‘71% of the participants had pelvic floor muscle tenderness, 66% had pelvic floor weakness and 41% were found to have a pelvic organ prolapse’(Dufour et. al 2018), further highlighting the importance of incorporating PFM in treatment. Arab et al. also examined PFD in women with and without LBP. The results show PFD in participants with LBP compared to those without. This is valuable for health care participants when assessment and treating LBP (Arab et. al 2010). It is also important to recognize PFD in pregnancy-related lower back pain (PLBP). Pool-Goudzwaard et. al discovered ‘52% of PLBP, significantly more than in the healthy control group’ (Pool-Goudzwaard et. al,2005) and promote addressing both LBP and PFD during pregnancy.

There are a variety of methods to help activate, strengthen and relax the pelvic floor in order to aid recovery in PFD. Kegels or reverse Kegels are often prescribed to promote awareness and strengthen PFM (Torgenu et. Al 2021). Transverse abdominus contraction has also been shown to help activate and strengthen PFM. Sapsford et al. found ‘that abdominals contract in response to a pelvic floor contraction command and that the pelvic floor contracts in response to both a “hollowing” and “bracing” abdominal command’(Mohseni-Bandepi et. al 2011), therefore proving the PFM can be activated by engaging the abdominals. Hypopressive exercises (HE) have also shown to aid recovery from PFD. HEs lowers the intra-abdominal pressure which enables an involuntary contraction of the PFM and transverse abdominus. Navarro-Brazález et. al suggests the combination of HEs and pelvic floor muscle training improves PFM strength and quality of life for patients with PFD (Navarro-Brazález et. al 2020).

Reference List

-

Arab, A.M., Behbahani, R.B., Lorestani, L. and Azari, A. (2010). Assessment of pelvic floor muscle function in women with and without low back pain using transabdominal ultrasound. Manual Therapy, 15(3), pp.235–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2009.12.005.

-

Bi, X., Zhao, J., Zhao, L., Liu, Z., Zhang, J., Sun, D., Song, L. and Xia, Y. (2013). Pelvic floor muscle exercise for chronic low back pain. Journal of International Medical Research, 41(1), pp.146–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060513475383.

-

Dufour, S., Vandyken, B., Forget, M.-J. and Vandyken, C. (2018). Association between lumbopelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in women: A cross sectional study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 34, pp.47–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2017.12.001.

-

Mohseni-Bandpei, M.A., Rahmani, N., Behtash, H. and Karimloo, M. (2011). The effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise on women with chronic non-specific low back pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 15(1), pp.75–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2009.12.001.

-

Navarro-Brazález, B., Prieto-Gómez, V., Prieto-Merino, D., Sánchez-Sánchez, B., McLean, L. and Torres-Lacomba, M. (2020). Effectiveness of Hypopressive Exercises in Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(4), p.1149. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9041149.

-

Pool-Goudzwaard, A.L., Slieker ten Hove, M.C.P.H., Vierhout, M.E., Mulder, Paul.H., Pool, J.J.M., Snijders, C.J. and Stoeckart, R. (2005). Relations between pregnancy-related low back pain, pelvic floor activity and pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal, [online] 16(6), pp.468–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-005-1292-7.

-

Torgbenu, E.L., Aimakhu, C.O. and Morhe, E.K.S. (2020). Effect of Kegel Exercises on Pelvic Floor Muscle Disorders in Prenatal and Postnatal Women – A Literature Review. Current Women’s Health Reviews, 16. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/1573404816999200930161059.