Plantar fasciitis: A common injury causing global heel pain

Photo by Tonnam Vongsamang on Unsplash

Plantar fasciitis holds the title as one of the most prevalent causes of heel pain across the globe. It is characterised by inflammation and causes severe stabbing pain that usually occurs with your first steps of the day. Movement does, however, result in a decrease in pain throughout the day. Although the underlying causes of this injury are poorly comprehended, it is more common in runners and older adults. Current statistics suggest that the prevalence of plantar heel pain in the UK population is 9.6%, with the population prevalence of disabling plantar heel pain at 7.9%.

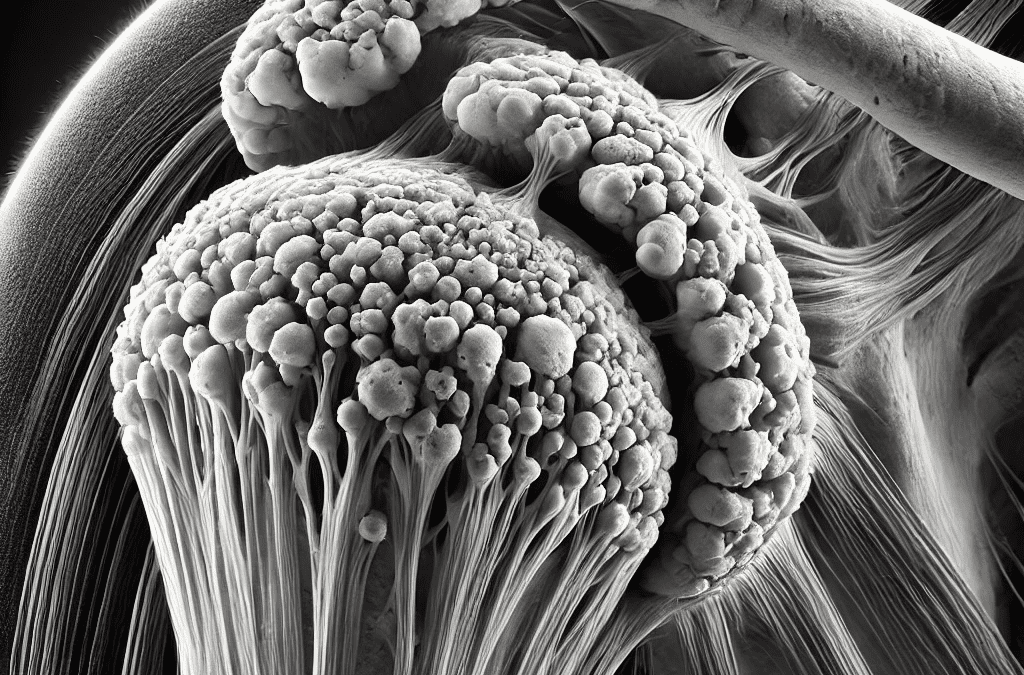

The plantar fascia is a band of tissue that connects the heel bone to the base of the toes, supporting the foot’s arch and absorbing shock with every step we take. However, prolonged tension and stress on this band of tissue can cause small tears. Alone, they do not cause significant injury, but repeated stretching and tearing of the fascia can cause irritation and inflammation, characteristic of plantar fasciitis.

Treatment of plantar fasciitis is varied and depends on the severity of pain experienced. There are remedies that can be adopted at home, or more specialist-focused approaches, including stem cell injections.

- Physical therapy is the most commonly adopted treatment option for plantar fasciitis; however, it does not fix the root cause of the problem, and many people experience recurrence of the pain further down the line. Exercises such as heel raise, floor sitting ankle inversion with resistance, seated toe towel scrunches, and plantar fascia stretches can all assist in easing plantar heel pain.

- Steroid injections, specifically cortisone injections, offer short-term pain relief of a few months. However, the risks associated with this method, including skin thinning, often deter people from taking this approach.

- Plantar fasciotomy is a surgical intervention that detaches the fascia from the heel bone in order to relieve tension and provide a long-term pain relief option. Despite this, only about 5% of those with plantar fasciitis choose this approach as it is only suggested if you experience persistent heel pain for greater than six months.

- Stem cell injections and platelet rich plasma form the regenerative approach to plantar fasciitis treatment. The goal of these interventions is to expedite your recovery journey and provide a therapeutic option with more long-lasting results. You can find more information on how these regenerative approaches work in our previous posts.

At Opus, we offer both platelet rich plasma therapy and stem cell therapy to combat your plantar heel pain. Get in touch to speak to one of our experts and begin your journey to pain free movement.